Note that this question is specifically focused on the random generation of the private keys and not on an individual actively targeting you and trying use knowledge of you or your public keys to steal your funds, we’ll cover that scenario in another Q&A.

This is quite a common worry and stems primarily from misunderstanding just how unlikely this event is to happen. The short answer to this question would be ‘it could happen, theoretically’. However, when considering ‘could happen’ we need to really look at the likelihood of it happening.

As Greg Foss (a well-known and passionate Bitcoiner) would say “It’s just simple Maths!”. Which is perhaps a more apt short answer to this question. Random things can happen, but for the most part we can be confident (based on how unlikely these events are to happen) that they’re not going to. We’re quite sure of this because we can ‘do the Math’.

Bitcoin generates addresses from private keys, which themselves are derived from a random number, that is between 1 and 2^256[*]. This is a very big number, so big that conceptualising it is difficult, so to help with this let’s consider these:

- The size of bitcoin’s private key space, 2^256 is approximately 10^77 in decimal (that is one hundred quattuorvigintillion). For context the visible universe is estimated to contain 10^80 atoms.

- A little closer to home what about grains of sand in the Sahara Desert? Well, there are estimated to be 1.504 * 10^24 (or one septillion five hundred four sextillion), which would mean we’d need 7.69 * 10^52 deserts full of sand. That is more deserts than there are grains of sand the Sahara!

- Or, what if you were to start a computer counting 1 number per millisecond? Well, it wouldn’t reach the end for 3.67 * 10^66 years (or three unvigintillion six hundred seventy vigintillion). Which, given the lifetime of our sun is just a mere 5 * 10^9 (or 5 billion) left, suggests we have much more pressing things to focus on!

A great example, for helping someone to understand the magnitude of this number, is one used by Yan Prizker in ‘Inventing Bitcoin’. Ask them to think of one completely random atom in the known universe and you try to guess which atom they are thinking of. Good luck!

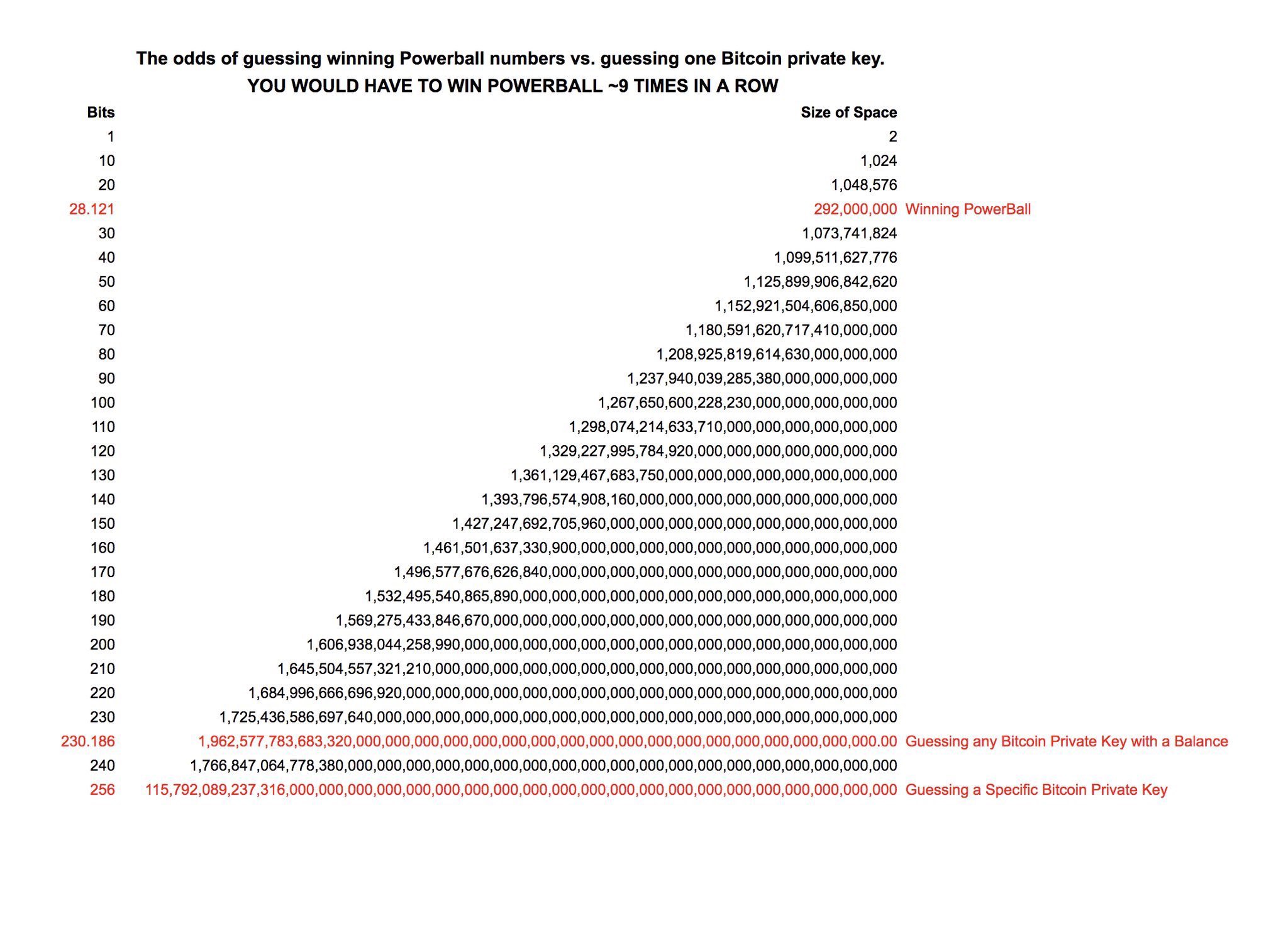

For another helpful visual comparison I recently saw a tweet with a very compelling image suggesting you would need to win the POWERBALL (which is no mean feat, at odds of 1 in 292,000,000) 9 times in a row to get even close to randomly guessing another person private key.

So, given that we know how unlikely it is for someone to randomly guess your private key, consider the level of security you would normally place on your finances. If someone picked up your debit card in the street, not knowing you or anything about you at all, the chance that they could put the card in a machine and randomly guess the 4-digit pin in one go would be a low as a 1 in 10,000 chance. Perhaps it is best to keep better tabs on your bank card, rather than worrying about someone guessing your Bitcoin private keys!

When it comes to key pair generation you could pick this number randomly yourself (but this is not advised as you’re never as random as you think you are). Instead, as is most common, most people use a device like a computer, sometimes in conjunction with your own additional input (like rolling dice/flipping coins), to generate this number in a way that cannot be repeated. It is important to know that this method is as uncertain and random as possible, which is why the number is not derived using a computer algorithm alone, but instead has added entropy from a range of internal and external sources (like temperature, user inputs, humidity etc.).

In reality, the incomprehensible vastness of this number in combination with the uncertain (or random) methodology by which it is generated stacks the odds in your favour. In fact, there are so many possible private-public key pairs that it is standard practice (for other security reasons that we’ll not get into here) to generate completely new keys and addressed for each transaction. The joy of which is that many signing devices (often mistakenly called wallets) do this automatically for you under the hood and keep track of everything, so you don’t have to.

[*] Strictly speaking the number is between 1 and n-1 where n=1.158 * 10^77, which is slightly less than 2^256. It is often much easier to present as simply between 1 and 2^256.

Additional Reading: